Old West Church, Boston, Massachusetts

Description and photos from a visit by M. Stone on April 28, 2000

The Old West Church at 131 Cambridge Street in the “West End” of Boston

My first objective that day was to visit the Old West Church, with which my great-great-grandfather, Lewis Humphrey Roberts, had supposedly been affiliated in his youth (according to his obituary).

I took the Green Line T trolley to Government Center, then got off and walked west along Cambridge Street. Within a few blocks I found the Old West Church, at 131 Cambridge Street, next to Lynde Street, and opposite very picturesque Hancock Street, which runs up Beacon Hill to dead-end at the Old State House. This is the church I had earlier determined was referred to in Lewis’ obituary, which states: “He was born of Welsh parents in Boston on February 26, 1831, the son of David and Catherine Roberts, in which city his early life was spent amid a coterie of noted American literary celebrities and statesmen. For a number of years he was organ blower [which means he pumped the mechanical bellows on the organ to supply it with air while the organist played the keyboard] for Rev. Dr. [Charles] Lowell, father of James Russell Lowell, in his church.”

Rev. Charles Lowell, D.D., pastor of the West Church from 1806 to 1861 (detail from a portrait hung inside the church sanctuary)

Here is a description and history of the church which I found on the back of a worship service program I picked up from inside the church (with typos and punctuation corrected by me):

“The West Church began on this site in 1737 in a wood-frame building. It became noted when its third pastor, Jonathan Mayhew, was among the first publicly calling for separation from England. Anticipating the revolution, British troops occupied the building and tore down the steeple to prevent signaling, [and] forced the pastor and church leaders to leave. [The British] later burned the building. Later the church gathered again and the present edifice was completed [in] 1806 as designed by Asher Benjamin, the first published American architect, with innovations later becoming standard. The West Church continued its social activism as shown by their donating some of the materials for the first African American Meeting House built nearby, by its integration and opening all seating racially (believed to be a first), and hiding fugitive slaves as part of the ‘Underground Railroad.’

“In early nineteenth-century Boston, this was one of the largest and most prestigious churches, first as Congregational, and later briefly [as] Unitarian. Here the first Sunday School in America was started by the Rev. Charles Lowell in 1812.”

I also found a note on an inside bulletin board claiming that Louisa May Alcott (one of my favorite American personalities) attended Sunday School at West Church. Born in 1832, she was a contemporary of Lewis Roberts, and spent the years 1834-1839, ages two to seven, in Boston while her father taught at the innovative school he founded at the Masonic Temple. Louisa spent most of the rest of her adult life in Boston as well, on and off, after 1849 (and died there in 1888), so she might have been a churchgoer at West Church around the time Lewis married Margaret Davies (December 1851) and in 1854 when he lived at 5 Mahan Place and worked as a machinist.

The West Church certainly seems to have been a hub in its community and nearby Beacon Hill. The Rev. Charles Lowell (indeed, he was the father of writer/editor James Russell Lowell) was pastor at the West Church for almost 60 years, from 1806 to 1861, according to the plaque on the front facade of the church.

Following the Civil War, its neighborhood in what would become known as the West End of Boston changed in character as new foreign immigrants poured in, and church membership fell off. The church closed its doors in 1889, and the building was bought by the City of Boston in 1891. Refurbished as a branch of the Boston Public Library, it served the West End in that capacity from 1896 until the 1960’s, becoming a central fixture in the neighborhood and known for its collection of Judaica. Presidential candidate John F. Kennedy (accompanied by Jackie) voted there in 1960.

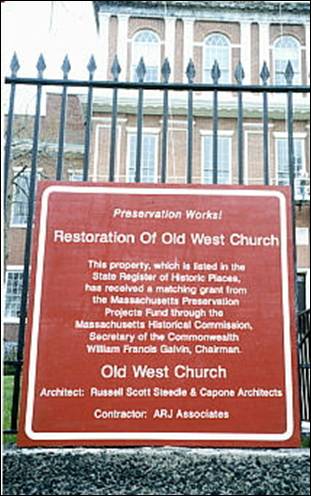

In 1964 two Methodist congregations (Copley and First Methodist, the founding church of Methodism in Boston, formed in 1792) united in the building as Old West Church United Methodist, which continues to this day. The church is a National Historic Landmark and its exterior at the time of my visit was being refurbished by work crews directed by the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (SPNEA) when I walked up (the second phase of the job was to be completed that May).

It was the highlight of my visit to Boston to see this almost-200-year-old church still being cherished, used, and improved, and to be able to easily imagine my great-great-grandfather a part of this church and this neighborhood (whether or not it really had been true). Next door to the church is the historic Harrison Gray Otis House (Otis was Boston’s third mayor and this house is now the headquarters of SPNEA), built in 1796, which would have looked much the same to Lewis Roberts in the 1840’s as it did to me that day. Unfortunately the rest of the neighborhood as far as the eye can see has changed dramatically, as urban renewal swept through the West End in the 1960’s and 1970’s and obliterated most of everything old to the east, west, and north of these two buildings.

View from the front walkway of the church in the spring of the year 2000: East up Cambridge Street toward Government Center (left); the view across Cambridge Street (center); west down Cambridge past Lynde Street (right). None of these buildings is as old as the church. Urban renewal swept almost everything away in the 1960’s.

Views of the Old West Church from Hancock Street. Next door to it is the Harrison Gray Otis House, built in 1796.

I took many photos of the church, exterior and interior. I found it charming, and I wish I could have visited it on Sunday during a worship service. Inside, the front of the church was decorated with still-pretty Easter lilies from the Sunday before. The interior of the square sanctuary was well-lit by the clear windows.

View of the back of the sanctuary shows the magnificent organ pipes and below, portraits of past ministers on the wall.

Interior views toward the front of the church and the altar area. Baptismal font (below), donated in 1854, sits in niche to the left of the pulpit.

One of the books I consulted described the architecture of the church this way: “a squarish meeting house with a rectangular block in front that rises up in several stages to a square-plan cupola….It has a certain charm, but it is entirely possible to imagine that its top and bottom were independently conceived. Inside, it’s a big square hall with a balcony running around three sides, very much a place for congregating. A large circle with a plaster-molded green fret inscribed in the ceiling emphasizes the centrality of the space, and the galleries are held by light-handed columns that have strangely attenuated acanthus-leaf capitals. Greek motifs, Congregationalist sensibility….[It is a] simple, fine and comfortable decorated brick box…” [Donlyn Lyndon’s The City Observed: Boston: A Guide to the Architecture of the Hub, Vintage, Boston, 1982].

In the entryway outside the sanctuary I found many interesting framed items on the wall, including old prints, photographs and building plans of the church and old maps of Boston. There is also a small meeting room and tiny kitchen area there, as well as stairs going up to more offices and the organ area.

Inside the sanctuary on the ground floor, at the back of the hall, are portraits of the church’s past ministers. Above, if you walk into the center of the sanctuary, you can see the back balcony and the pipes of the beautiful twenty-nine stop Fisk organ which was installed on the existing organ piers in the 1970’s. The old-fashioned, beautiful wood cases around the organ pipes, found in Ipswich Massachusetts, were, after being renovated, discovered “to have been the work of Thomas Appleton, an organbuilder whose workshop had been located just a block down the street from West Church during the 1830’s.” I began to get goosebumps wondering how much of this church I was now viewing had also been viewed by Lewis Roberts. I climbed up the worn, bowed, wooden stairs to the organ loft, thinking his feet might have preceded mine there. It was a thrill even though the doors at the top of the stairs were locked.

Old West Church is currently the home of the New England Conservatory Organ Department and the Old West Organ Society, so it is nice to see that Lewis’ supposed tie to this church (the organ) is still one of its strong points.

There is probably no way I can ever determine if Lewis was actually the “organ blower” for Rev. Lowell, for such a minimal role has not merited inclusion in the only surviving church records I’ve found (LDS FHL microfilm no. 856695, Item 2, “West Church records; baptisms, marriages, 1737-1880”). Even if this “organ-blower” detail was a fabricated bit of color in his obituary (as is the whopper told there about his having been wounded at the battle of Chancellorsville), I tend to think there is probably a grain of truth somewhere behind it. If he was not actually organ blower (and probably not much involved in the “coterie of noted American literary celebrities and statesmen”), he probably at least at one time almost certainly knew the neighborhood and knew enough about the church and Rev. Lowell to have claimed a tie. And if he was indeed an “organ blower” as a youth, it may have been his first introduction to machines and their operations that allowed him to pursue his lifelong occupation of “machinist.”

When I finally left the church, I walked up Hancock Street, wandered my way over Beacon Hill and down to Beacon Street and the Boston Common. There was the Frog Pond that Louisa May Alcott had fallen into at age four (now being drained and cleaned). Trees, tulips and daffodils were in bloom. I don’t think the essence of the park has changed that much from when Louisa and Lewis strolled there.

Views from the west (Lynde St. side) and from the east (Staniford Street side)

You can read more about the history of West Church at the current website of Old West Church United Methodist.

You can see more old photos of West Church, Louisa May Alcott’s home, and other Boston landmarks at The Bostonian Society’s online digital photo and postcard collection.

| BACK to Lewis H. Roberts page |

| Home |