« BACK

Lewis Humphrey Roberts (1831-1915)

continued...

MILITARY SERVICE: Civil War veteran

Summary of service:

Private, 7th Battery, Wisconsin Volunteers, Light Artillery (“The Badger State Flying Artillery”), 11/14 November 1861 to 18/20 November 1862.

Private/Sergeant, Invalid Corps / Veteran Reserve Corps (V.R.C.), 18 September 1863 to 31 August 1866. Company C, 13th Regiment I.C., Camp Sumner, Wenham, Massachusetts, and later Galloups Island (Headquarters Draft Rendezvous), Boston Harbor, Massachusetts. Transferred to 6th Independent Company, V.R.C., 23 December 1865.

Private/Sergeant Major, Veteran Reserve Corps / U.S. Army, 6 May 1867 to 13 April 1869. Enlisted in Boston, Massachusetts; transferred to Madison Barracks, Sackets Harbor, New York arriving 21 June 1867; assigned to Company K, 42nd Regiment U.S. Infantry, Madison Barracks, Sackets Harbor, New York on 10 January 1868. Discharged on disability 13 April 1869 from Madison Barracks, New York.

At various times as he grew old, he stayed at both the Soldiers and Sailors Home at Bath (Steuben Co.), New York, and the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (Southern Branch), aka “National Soldiers Home,” near Hampton (Elizabeth City County), Virginia, where he remained “on furlough” for some 14 years even while living back home in Jefferson County, New York.

Details of service:

The opening shots of the Civil War were fired at Fort Sumter, Charleston, South Carolina, on 12 April 1861. Seven months later, on 11 November, Lewis Roberts, according to Union records, a 30-year-old, married machinist living then in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, enlisted as a private for a three-year-hitch and arrived three days later at Camp Utley near Racine, Wisconsin, with Captain Richard R. (“Old Dick”) Griffith’s 7th Battery, Wisconsin Volunteers, Light Artillery (“Badger State Flying Artillery”).

The term “flying artillery” was used mostly by the Rebel forces, but it also existed in the North. It meant a battery (cannon) designed to race from place to place and to be set up quickly on the field of battle—fire a few well-aimed rounds—and then “fly” to another part of the field and do it all over again. Flying artillery units usually operated on horseback; every man rode, the guns were also pulled by horses, and all could keep up with the cavalry. This was done in an attempt to avoid the deadly counter-battery return fire of the enemy.

Lewis H. Roberts’ unit, which had been mustered into the service of the U.S. on the 4th of October, spent the winter getting acquainted with military life and learning how to fight. The Federal government took over the operation of the training camp from the state of Wisconsin in January, 1862. Meanwhile the soldiers trained at Camp Utley and awaited the paymaster and their marching orders. There were two gunnery ranges outside of nearby Racine. During the winter months the five companies of artillery at the Camp would practice shooting at the ice formations out in Lake Michigan. On holidays, they hauled their cannons downtown and blasted them for the amusement of the locals.

The Badger State Flying Artillery (7th Battery) finally left Wisconsin on 15 March 1862,

when, with the Fifth and Sixth batteries, they proceeded to St. Louis…On their arrival at St. Louis they were ordered to report to General Pope, at New Madrid [Missouri], the siege of Island No. 10, then being in progress. Moving down the Mississippi River, they landed at Cairo, and proceeded by rail to Sykestown, on the Fulton and Cairo Railroad. From Sykestown, they marched to New Madrid, reporting on the 21st. Here they were employed in the construction and repair of the fortifications along the river, the place having recently been evacuated by the rebels. Detachments were placed in charge of some of the siege guns. After the surrender of Island No. 10, the Seventh Battery was stationed at Fort Bankhead, Fort Harney, and Fort Thompson, near New Madrid. They subsequently moved to Island No. 10, where, on the 13th of June, they received orders to move to Union City, which they reached the next day.

The battery had been furnished with horses and guns before they left Island No. 10. At Union City, they joined the brigade of General R. M. Mitchell. The battery was stationed, during the summer and fall, first at Trenton, and then at Humboldt [Tennessee], engaged in railroad guard duty.

[The Military History of Wisconsin… by E. B. Quiner, 1866, pages 950-951.]

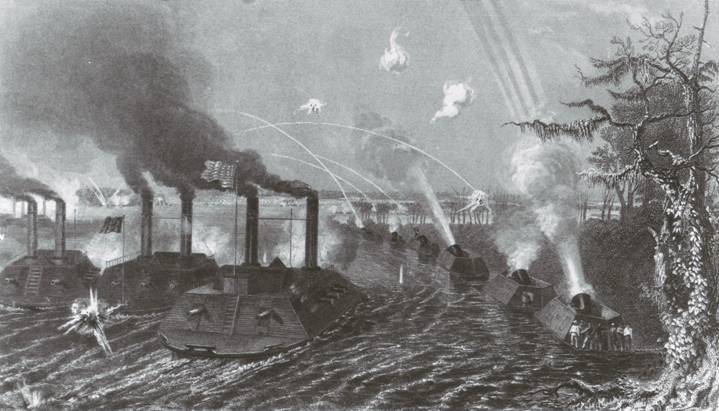

The Battle of Island No. 10. Photo credit: Massachusetts Commandery Military Order of the Loyal Legion and the US Army Military History Institute.

What became known as the Battle of Island No. 10 was part of the general southward push of Union forces leading to the Battle of Shiloh, and involved the capture of entrenched Confederate positions blocking the S bend of the Mississippi River around New Madrid, Missouri. Island No. 10 (the tenth island south of the Ohio River’s juncture with the Mississippi) held a fort protected by 19 Confederate guns and 7,000 troops, supported by batteries on the Tennessee side of the river and a fleet of gunboats on patrol. The Northern forces included 20,000 troops, six ironclad gunboats, and 11 mortar boats. After a few false starts (including three weeks of hacking alternate routes through swamps and marshes) the Federal troops defeated the Rebels and seized control of the Island and that stretch of the Mississippi River, in what could only be termed a stunning victory: over 5,000 Confederates, including three generals, were taken prisoner, with only a handful of Federal troops lost.

After helping to win that decisive battle, the Seventh Battery was transferred south and assigned to forces operating in middle Tennessee. For some months later (according to a Certificate of Service for Lewis Roberts issued May, 1994 by the Wisconsin Veterans’ Museum), “the Seventh Battery was engaged in active pursuit of rebel raiders in [the woods and along the railroads in that area of] Western Tennessee.” The so-called Battle of Corinth [Mississippi] took place near there on 3-4 October 1862, and although one of Lewis’ four obituaries claimed he received a near-fatal head wound there, there is no evidence that Lewis Roberts’ particular Army unit was engaged in the battle of Corinth itself. However, General William S. Rosecrans was in command of this engagement at Corinth, and it is at this point that Lewis Roberts might possibly have been “promoted to mounted orderly on the staff of General Rosecrans” as his obituaries claimed.

The Seventh Battery, Wisconsin Volunteers, would go on to participate in action at Parker’s Crossroads on 31 December 1862, and after that, from its Jackson, Tennessee headquarters, would accompany expeditions into various parts of western Tennessee and northern Mississippi. It would be stationed at Corinth, Mississippi for a short period in June 1863, and later that same month would be transferred to Memphis, where it remained headquartered throughout the remainder of the war.

But almost exactly one year after Lewis Roberts had enlisted, he was “discharged for disability,” seriously disabled and unfit for further active service, and he left the Seventh Battery for good on Tuesday, 18 November 1862 near Humboldt, Tennessee. (See more on the nature of his disabilities below.)

Thereafter, by his own account (in pension papers), following his disability discharge, Lewis Roberts went to live with his older brother, Dr. David Roberts, a physician and apothecary, and stayed with him and his family at his home near the corner of Dorchester and Fourth in South Boston, Massachusetts, until the following summer. David ran a drug store at that location, and tried to treat his brother’s medical conditions but, as Lewis Roberts would state later in life, “...my brother...told me that no treatment would help me.”

I have not yet found out why Lewis did not return to Wisconsin, or to his wife, Margaret. She remained in Milwaukee, running her boarding house and living with (and being supported at times by) her brother, William. For the first few years after the war, she was listed in the Milwaukee city directories as a widow. But she later filed for and was granted a divorce from Lewis in 1870 on grounds of desertion. She claimed Lewis had left her for good, gone to Boston, and cut off all subsequent contact with her on 25 August 1859. Coincidentally or not, that date was two days following the death of his brother David’s wife, Ellen, in South Boston. Could that news, brought by telegraph wire, have prompted him to bolt for the East Coast as Margaret claimed he did? And was he really back in the boarding house in Milwaukee in time for the 1860 census-taker, before enlisting in the Army in Milwaukee in 1861? These questions cannot be answered. But the divorce papers do reveal that Lewis and Margaret had no children. Whatever their troubles together were, they had no descendants made to suffer by them.

Re-enlistments and court-martials

Although Lewis’ obituary would claim that he “was wounded at the battle of Chancellorsville” (Virginia, 1-3 May 1863), this seems most improbable, and was never so claimed or even mentioned by Lewis Roberts himself in any of the many pension documents he submitted, which I have examined. On the contrary, Lewis was quite clear about stating that he was living with his brother in Boston and was severely disabled during the time when the battle of Chancellorsville took place. He was almost certainly NOT at the Battle of Gettysburg either (which took place in Pennsylvania on 1-3 July 1863), as his daughter, Clara, would later claim (Watertown Daily Times article, 6 August 1938). I think it is reasonable to assume that his daughters, after his death, mistakenly placed him at the battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, and that Lewis would have corrected them by telling them it was the (by then) less-renowned Battle of Island No. 10 at which he fought (as he correctly noted in his pension application papers).

Sadly, Lewis’s brother, Dr. David Roberts, died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 36 in South Boston on 15 August 1863, leaving behind his second wife, Mary, and three small sons (one of whom was “Idiotic & blind,” according to the 1860 census). Lewis Roberts soon made the decision to re-enlist in the Army, and joined up again in Boston, Massachusetts for a term of three years, on Friday, 18 September 1863 as a private in the “Invalid Corps” (later officially named the Veteran Reserve Corps, or “V.R.C.”). The Invalid Corps was a branch of the Union forces for disabled soldiers who still wished to serve their country.

Many years later, when he was applying for his invalid pension in 1887, Lewis Roberts recalled that his disabilities when he joined the Invalid Corps were such that he was unable to “carry a musket” from the time of his enlistment until he left the service because “my condition was such that I could not hold a gun” due to a paralysis of his right side. But on the day of his enlistment in Boston the accompanying doctor’s certificate read:

I CERTIFY, ON HONOR, That I have carefully examined the above-named [left blank] agreeably to the orders and instructions establishing the Invalid Corps; that his present infirmity is Loss of sight of right eye, consequent upon gunshot wound received at battle of Corinth. and, in my opinion, he is not physically or mentally disqualified for performing the duties of a soldier in the Invalid Corps.

(signed) Jos. H. Streeter, Surgeon

And Lewis signed the following statement on 18 September 1863: “I, Lewis Roberts, desiring to enlist in the INVALID CORPS, for the term of 3 years, DO DECLARE, That I am 32 years and 8 months of age; that I have been honorably discharged the service of the United States on a former enlistment by reason of disability; and that I know of no impediment to my serving honestly and faithfully in the Invalid Corps for 3 years.” He was certified to be “entirely sober when he enlisted” by the recruiting officer, and was duly mustered in.

On 8 November he was transferred from an unassigned detachment of men at Depot Camp, Wenham, Massachusetts to Company C, 13th Regiment I.C., stationed at Camp E.V. Sumner in Wenham. This company (under the command of Captain Horace Neide) was immediately transferred to Beach Street Barracks in downtown Boston, and later to Galloups Island (Headquarters Draft Rendezvous), Boston Harbor. (I believe this latter place is now known as Gallops Island, and is part of Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area.

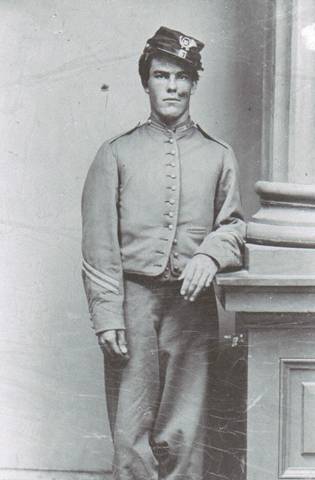

Two unidentified enlisted men in the Veterans Reserve Corps. The one on the

left was in the 13th Regiment V.R.C., the same regiment in which Lewis Roberts

served. Photo credit: U.S. Army Military History Institute.

On 28 November 1863 Lewis’ 57-year-old father, David Roberts, died of chronic heart disease in Boston. This happened just a few months following the untimely death of Lewis’ brother, Dr. David Roberts, and the death of Dr. David’s two-year-old son, Albert, on 23 September, just days after Lewis had enlisted in the Invalid Corps (all three are buried at Mt. Hope Cemetery in Mattapan, Massachusetts).

Shortly thereafter, Lewis Roberts was reported absent and as being in Mason General Hospital, Boston, on the Invalid Corps company muster roll for January and February, 1864. Although he could have been there as a patient, it is just as probable that he was assigned there as a worker in the Invalid Corps, for these disabled soldiers were assigned to work at hospitals and military installations as cooks, bakers, carpenters, orderlies, clerks, etc. The records kept then were very sketchy indeed; officers were directed to account for their men absent on such assignments by total number only, not even by name.

However, Lewis Roberts was reported as “deserted” on an expired furlough pass from 13 June to 21 July 1864, and was apprehended in Boston. A much later document from 1888, clarifying that this charge of desertion had been reduced to one of being “absent without leave,” describes the case as follows:

He was tried before a general court martial for desertion...having received a furlough from Draft Rendez-vous Galloups Island, Boston Harbor, which expired on the 13th day of June, 1864, did fail to return at the expiration of said furlough, and did desert said service, and did remain absent without leave from proper authority until apprehended as a deserter at or near Boston, Mass. on or about the 19th day of July, 1864....Thirty dollars paid for his apprehension. He was found not guilty of desertion but guilty of absence without leave and sentenced to forfeit $10 per month of his monthly pay for four months and be confined at hard labor during the same period at such place as the Commanding General shall direct. The proceedings, findings, and sentence were approved and promulgated in G.O. No. 66 Hd Qrs Dep’t of the East New York City, September 6th 1864.

From my study of the records, it seemed to be extremely common at that time for the men of the Invalid Corps to “fail to return at the expiration of” their furlough passes. Every month or so a regimental court-martial was held to judge, sentence, and punish anywhere from three to 20 men (usually privates) of the 13th Regiment for doing just that. The usual punishment for such a crime was a fine of between five and 15 dollars and confinement for three to 15 days. Detailed records of the proceedings of Lewis Roberts’ general court martial (a more serious proceeding than a regimental court-martial) do not exist, and I am mystified as to why his jurisdictional review and punishment in this case were so severe. Nor have I a guess as to why he went AWOL (though given the nature of his disabilities, the proximity of former friends and family, and the administrative chaos of the newly-organized Invalid Corps, I am quick to sympathize).

Perhaps the recent deaths, the loss of a parent and the brother he had relied on, and the subsequent bereavement of Dr. David’s widow and small children may have had something to do with Lewis overstaying his furlough. Perhaps he was annoyed at not receiving his pay from the Army (this was a common occurrence). Perhaps family members or friends needed him, or persuaded him to stay away; perhaps he fell in with bad company or gave in to bad habits of “dissipation” or drunkenness. (There were continual court-martials and citizens’ complaints taking place concerning drunk and disorderly conduct, soldiers annoying and “committing depredations” upon the citizenry, loitering, wandering off without passes, and “inciting the company to disaffection”). Or perhaps Lewis Roberts had trouble of a personal nature with one or more of his superior officers. We can only speculate.

The war ended a few months later, on 9 April 1865. The following month, on 1 May 1865, Lewis Roberts was recommended for promotion by his commander, Captain Andrew C. Bayne, and rose in rank from private to corporal. But he was again reported “absent without leave” in Boston, from 26 June to 1 July 1865. At his second (regimental, this time) court-marital held on 13 July 1865 he was fined eight dollars and reduced to the rank of private. Military laws concerning these jurisdictions and punishments had been changed and standardized since his previous court martial.

It appeared that Lewis Roberts had now found some friends in the upper ranks to look out for him. On 23 December 1865 he was transferred to the 6th Independent Company, V.R.C., where he served as orderly for Major F.N. Clark of the 5th U.S. Artillery, Provost Marshall General of Massachusetts, in Boston (who, incidentally, was acting commander of the entire Invalid Corps at one time). On 1 August 1866 Roberts was appointed to the rank of sergeant and on Friday, 31 August he was discharged and mustered out at David’s Island, New York Harbor. He was just a few days shy of completing his three-year-hitch, and the reason given in his medical records for his discharge on disability was that he had diarrhea. Such a medical condition in the 1800’s could indeed have been life-threatening, and could be a result of poor nutrition, infection, dysentery, or malaria. He could have been near death and discharged as unfit for further service, even in the Veteran Reserve Corps. Or, such a condition could have merely been a medical reason to obtain a disability discharge and perhaps facilitate a present or future disability pension (the General Pension Act of 1862 provided disability payments based on rank and degree of disability). That he was transferred to and discharged from a military facility in New York City (and then chose to pass the winter there) perhaps indicates that he may have had friends in New York and that someone seemed to be doing him some favors. Or at least we can hope so.

Certain aspects of military life must have agreed with him (or else he had few other prospects), for one year later, on Monday, 6 May 1867 Lewis Roberts re-enlisted as a private (why not as sergeant, his prior rank?) in the Veteran Reserve Corps at Boston for three more years. On 20 June his detachment left Fort Columbus, New York Harbor at 7 a.m., catching the steamer C. Vibbard at 8:30 a.m., which took them from the landing at the foot of Desbrosses Street in New York up the Hudson River to the town of Athens, New York, arriving at 5 p.m. From there they probably traveled “via Rome to Watertown, N.Y. over N.Y. Central and Rome, Watertown & Ogdensburg Rail Road,” arriving at Rome at 11:00 p.m. and catching the next morning’s train at 4:30. They arrived in Watertown in Jefferson County at 8 a.m., 21 June, and marched to the military installation known as Madison Barracks, 10 miles west, adjacent to the small village of Sackets Harbor on Black River Bay, arriving at 1 p.m. the same day.

“Old Stone Row” at Madison Barracks, near Sackets Harbor, New York.

These stone buildings were constructed as officers’ quarters by the

2nd U.S. Infantry between 1816-1819 as part of a permanent safeguard

against

attack from the north after the War of 1812. Ulysses S. Grant lived

here for four years after

graduating from West Point. Today Madison Barracks

forms

a National

Register Historic District. Photo

by M. Stone, 1994.

Click here for background info on Madison Barracks while Lewis Roberts was there.

He remained an unassigned recruit at Madison Barracks until the following January, when Company K was organized as of 10 January 1868. Company K consisted of forty enlisted men transferred from other companies and ten unassigned recruits (including Lewis) stationed at Madison Barracks. Upon assignment he was also promoted to sergeant (10 January 1868) and was listed as being on daily duty as clerk at regiment headquarters. He later described his job there as being connected with the adjutant’s office (his obituary described him as regimental bookkeeper).

On 5 August 1868 per Standing Order 84, Lewis Roberts was (once again) reduced to the rank of private, reason unknown, but still remained on daily duty as clerk. Three days later, on 8 August 1868 he was married to Ellen A. Roberts in Watertown. It was probably at Madison Barracks that Lewis met Ellen, who lived in the adjacent small town of Sackets Harbor and worked at the “Camp Home,” a facility at Madison Barracks, according to published recollections of their daughter, Clara.

On 21 November 1868 Lewis was promoted once again to sergeant, retroactive to November 1st. On Friday, 1 January 1869 he was promoted to sergeant major and transferred out of Company K to non-com staff. On 13 April 1869 his former company, Company K, left Madison Barracks, headed for St. Louis, Missouri and its new home at Fort Gibson, Indiana along with commander Andrew C. Bayne, Lewis Roberts’ former commander (and friend?) from Boston. On that same day, Lewis Roberts was discharged for disability with the rank of sergeant major and was paid a bounty of $55.00 to boot. Thus ended his military career, and he became a civilian.

In 1887, some 18 years after leaving the service, Lewis applied for his original Invalid Pension, which was granted. As mentioned above, the Army in 1888 clarified for pension purposes that his 1864 court martial in Boston for desertion resulted in a conviction on the lesser charge of having been “absent without leave.”

As he evidently became more disabled as the years went by, he stayed at the Soldiers and Sailors Home at Bath (Steuben County), New York (February through May(?), 1888) and also at the “National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (Southern Branch),” aka the “National Soldiers Home,” near Hampton (Elizabeth City County), Virginia (1890). He remained “on furlough” from the latter facility for some 14 years even while living with his wife and family in Watertown, New York.

Veterans’ Administration Building, Bath, New York. This was once the “Old Soldiers’ Home” where Lewis Roberts convalesced circa 1888. The building’s façade reads “1877” and “G.A.R. Soldiers’ Home.” The G.A.R., or Grand Army of the Republic, was a Civil War veterans’ organization. Photo by M. Stone 1995.

Details of his disability and pension:

According to his obituaries, Lewis Roberts was said to have served “in the great southwest campaign under Grant, being promoted to mounted orderly on the staff of General Rosecrans....He was wounded at the battle of Chancellorsville and at the battle of Corinth he was struck in the head by a piece of shell, the result being nearly fatal. He was then discharged for disability and returned to Boston....Later he enlisted in the service and was detailed to Sackets Harbor, where he acted in the capacity of regimental bookkeeper for several years....”

But what his invalid pension records show is that in October 1862, near Humboldt, Tennessee (not far from Corinth, Mississippi), at the approximate age of 31, he was stricken with partial paralysis of the right side, hand, arm, and leg, along with blindness in the right eye and deafness in the right ear. Though his infirmities were never in doubt, there were various explanations and descriptions for them, from various parties, no doubt with various motives:

Nov., 1862, Certificate of Disability for Discharge: On the immediate scene, Capt. R.R. Griffith, Lewis Roberts’ original commander from Wisconsin, states in this official document that Roberts had had severe head pains since the previous July; the Battery Surgeon of the field hospital further describes Roberts’ condition as follows: “The cataract [in his eye] was caused by a cinder of iron cutting through the capsule, Before entering the U.S. service and has since rendered it opake. He had a partial shock of palsy on the 28th of October 1862 which impaired the use of the muscles on the right side of the body for four days. It was not feigned. Symptoms of approaching apoplexy have attended him for the last two months, and prophylactic treatment used. He has been unfit for duty much of the time through the summer, and I believe he will never be fit for military duty. I believe the cause to be hereditary predisposition which will render him subject to attacks in any employment.”

1869, Military discharge report from the V.R.C., Sackets Harbor, NY: Seven years later, long after the war ended, talk of a distinct wound appears: “Said Lewis Roberts was injured while in the line of duty in the U.S. Army, near Island N# 10, Tenn. April 1862, causing varicocele of right-side, and received a shell wound of forehead causing loss of sight of right eye near Corinth Miss, Oct. 1862.”

1887: Lewis Roberts, in an affidavit in support of his invalid’s pension application, does not mention a wound, but states that his paralysis and blindness were due to “exposure and hardship with his Battery at near [sic] Humboldt Tenn.”

Jan. 26, 1888 letter from the War Dept., Adjutant General’s office to the Commissioner of Pensions, gallantly describes his “disability...loss of sight of right eye consequent upon a gunshot wound received at [the] battle of Corinth.”

His deafness could well have been a result of being an artilleryman in the Badger State Flying Artillery (working next to the big wheeled cannons), but Lewis Roberts never claimed that reason specifically.

Whether his infirmities were due to gunshot or shrapnel wounds, during the war or prior to it, or a “near-fatal” wound to the head, or whether they were actually due to some sort of stroke, epilepsy, apoplexy, or “hereditary” weakness or palsy, there was no doubt that they were largely incurred during and exacerbated by his military service. (It is interesting to note that his older brother, Dr. David Roberts, had died in the course of one day in Boston in 1863 due to “congestion of the brain”—also apoplexy, epilepsy, or stroke?—at the age of 36.)

Lewis Roberts was granted a military invalid’s pension based on his active Civil War service, which he drew from 1887 until his death in 1915. In response to his Declaration of Original Invalid Claim (Certificate No. 407,358) filed 16 June 1887, he was pensioned at $8 a month for “partial paralysis of right side.” This payment was increased to $16 a month on 24 April 1889, and to $17 a month on 27 July 1892, for the total loss of right arm, hand, and leg, loss of sight in right eye and severe deafness of right ear. His pension payment was increased to $30 a month on 12 July 1899 and remained at that level until his death in 1915. His widow, Ellen Roberts, applied for and received a Civil War widow’s pension until her death in 1923.

| Home |

Rev. 22 August 2007

Copyright

2007 Michelle Stone. All rights reserved. This information may be used for

personal and/or scholarly research only. Commercial use or reproduction of any

information contained on this website is strictly prohibited. Information

contained on this site is not to appear on any web site on the Internet or in

any printed format without written permission. Please link to my site and give

appropriate copyright credit. Thanks!