PETER DEMARE (c. 1820 – before 1880?)

and SOPHIA LANDMAN (c. 1835 – before 1870?)

and their descendants

updated 18 November 2014

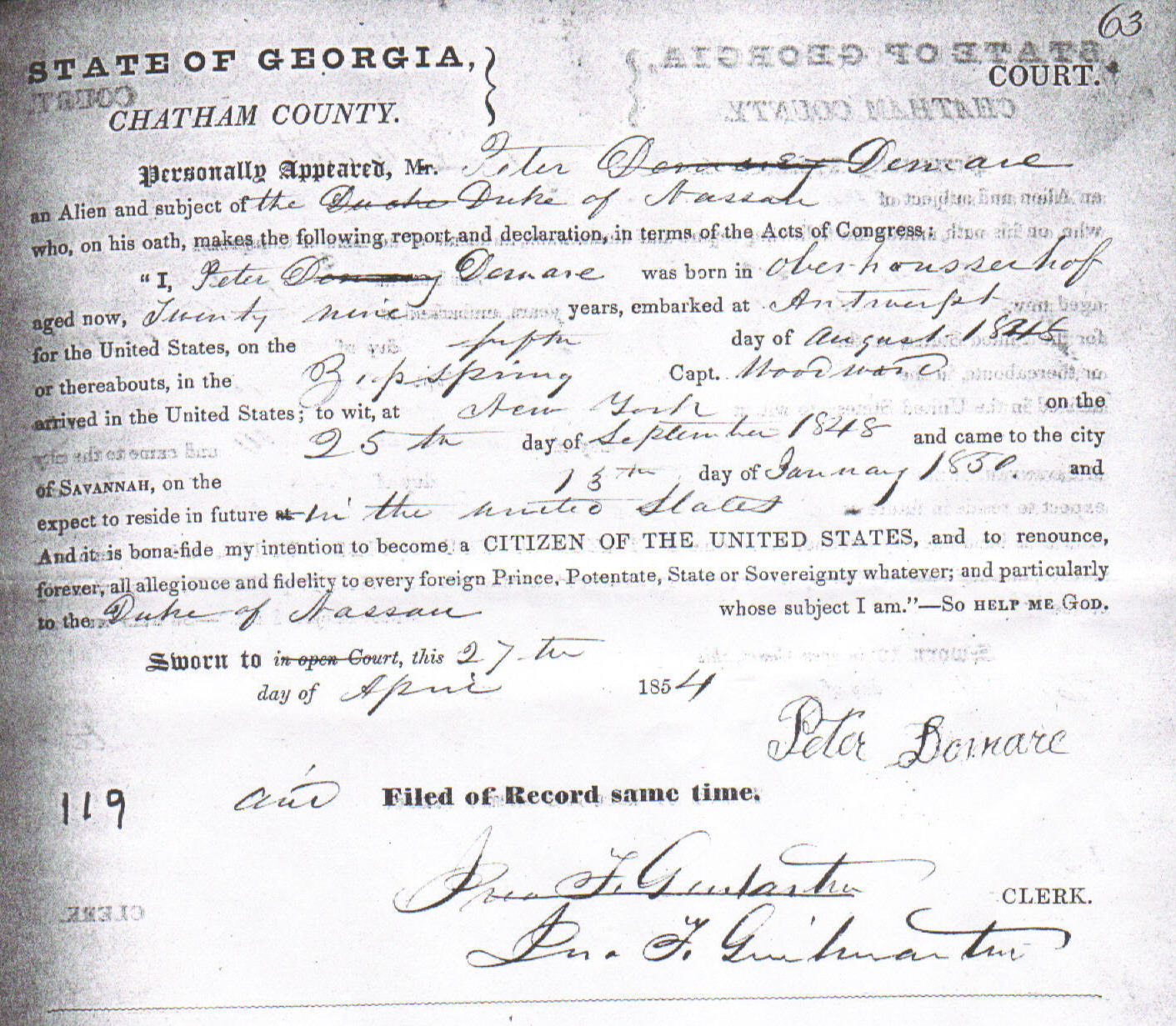

PETER DEMARE, “an Alien and subject of the Duke of Nassau,” claimed to have been born at “oberhousserhof” when he filed his declaration of intention to become a U.S. citizen at the Chatham County courthouse in Savannah, Georgia, U.S.A. on 27 April 1854.

The person filling out the form twice misspelled Peter’s surname as “Demarey” and twice was the mistake struck out and corrected. Peter could read and write and had no equivocation in spelling his own surname at the bottom of the form:

but we are left with the impression that the surname as heard by the court clerk that day had been delivered with a French pronunciation (as if it had originated centuries before as Demarée or Demarest). That day Peter, most probably dictating the information to the clerk in a distinct German accent, was getting his inevitable share of American officialdom’s mangling of his identity.

As a subject of the Duchy of Nassau, Peter had emigrated from what is today the western-central portion of Germany (annexed by Prussia in 1866 as the province of Hesse-Nassau and today a part of the province of Rheinland-Pfalz). Peter also that day claimed to be 29 years of age, and stated with emphatic particularity that he had embarked from the port of Antwerp on the fifth day of August 1848 aboard the ship “Zipspring” under a Captain Woodward, and had arrived at New York on the 25th day of September 1848.

Finally, he recorded that he had come to the city of Savannah four years earlier (to be precise), on the 15th day of January 1850, and wished to become a United States citizen, renouncing “forever all allegiance and fidelity to every foreign Prince, Potentate, State or Sovereignty whatsoever; and particularly in the Duke of Nassau whose subject I am. So Help Me God.”

With this oath sworn to and this document then duly filed at the courthouse, Peter had started the process of required paperwork for becoming a citizen of his new, adopted homeland.

What happy fortune for a genealogist-descendant to uncover a document offering so many details! For several years I (Peter’s great-great-granddaughter) searched for confirmation of the claims in this document. Frustratingly, I never found any mention, anywhere, of a ship named “Zipspring.” It did not turn up where expected on the Port of New York passenger arrival lists microfilmed by the National Archives. Nor has it yet appeared anywhere on the internet’s multiplying sources. I found no mention of a Captain Woodward piloting ships from Antwerp or Germany to the United States during that time period. What I did finally discover, however, was that a Peter Demare was listed on the passenger manifest of the ship “Seth Sprague” (598 tons) piloted by Captain Alex. Wadsworth from Antwerp to New York, arriving 21 September 1850 (two years later than Peter claimed). Peter was described on this ship’s list as being 30 years old and a farmer from Germany. All the other passengers, including all the women listed on the manifest, were also described as being farmers from Germany, which gives an idea of how casually the list was compiled. Only names and ages were particularly listed, and Peter Demare would seem from this list to have been traveling alone, and was enumerated among other evidently single people. There were no other Demares on the boat.

I have learned and been told that many men fled Germany in 1848-1849 to avoid persecution, forced military service, or death during the aborted German “democratic revolution.” Many fled the country in secret or illegally, and perhaps Peter, lagging behind the bulk of the emigrant wave of fleeing revolutionaries, had been one of them. The widespread crop failure in 1847 and resulting famine could have been another reason to make him go. Perhaps he did deliberately provide false information on his naturalization petition in order to hide his trail or maybe it was just a simple mistake made either by him or by the person filling out the form.

His age given in this declaration of intent with its implied birth-year of 1825 falls under question as well. The “Seth Sprague” manifest and U.S. documents that followed in later years would make him out as being older than this initial claim, yielding a birth year that varied somewhere between 1820 and 1825. These variations throw more doubt on the reliability of all of the information given in his naturalization petition.

But surprisingly, there is indeed an “oberhousserhof” within the boundaries of the former Duchy of Nassau’s territory. East of the Rhine, south of Limberg and north of Wiesbaden, near the town of Burgschwalbach in the Rhine-Lahn-Kreis, along the road between Burgschwalbach, with its medieval castle and the neighboring town of Panrod (all in the beautiful Taunus region of rolling fields and deep forests) there is an ancient farm estate called Oberhäuserhof, where at least one family of Demares did live and work as farmers in the 1800’s. Other Demares, Demarées, and Demmers lived in the nearby towns of Daisbach, Aarbergen, Burgschwalbach, and Kettenbach. Given the apparent French origin of the surname, these families could originally have been among those refugee French Huguenots (Protestants) driven from Catholic France beginning in the late 1500’s who found sanctuary in Germany, Switzerland, Holland, England and in the British American colonies.

But here again, disconcertingly, no documentation of my Peter Demare’s birth has yet been found where expected among the copious German Demare vital records of that time and place that have been microfilmed by the Morman church—although a Peter Demare who could have been my ancestor was named as godfather at the baptisms of three namesake baby boys all born at Oberhäuser Hof in 1838, 1845, and 1847.

It is one of those mysterious “brick walls” that (temporarily or permanently) stump genealogists. I hope to continue research to discover my great-great-grandfather’s true roots, circumstances, motivations, history, and family in Germany (and possibly France).

Meanwhile, in Savannah, Georgia, Peter Demare seemed to be finding success in life. He survived the terrible yellow fever epidemic that swept through the city during the summer months and the devastating hurricane that hit in September following the filing of his declaration of intention in 1854. Two years later, he applied for a Chatham County marriage license on 20 January 1856, naming as his bride SOPHIA LANDMAN (a 21-year-old girl said to be from Hanover, Germany, about whom I have as yet found very little family information). Once again Peter’s surname in this document was (mis)spelled in the way of the French pronunciation, “Demery.” The date, place, and minister for the wedding were not indicated for this couple, and have not yet been found elsewhere.

Just a few months later, on the 12th of May 1856, the newlyweds were granted U.S. citizenship when Peter took the oath of allegiance in open court before Judge John Miller along with five other immigrant men from Great Britain and Ireland, Prussia, and Hesse-Darmstadt. (During that time period, wives and minor foreign-born children received U.S. citizenship when their husbands or fathers were naturalized.) This time Peter was erroneously indicated in the court records as the first name in a brief list: “Peter Demere an alien and a Subject of the Queen of Great Britain & Ireland.” Sandwiched between other court proceedings that day, the ceremony must have been swift and perfunctory—otherwise Peter might have had time to check and correct the spelling of his surname and the clerk’s assumption that Peter was kin to the numerous prominent local Demeres (descendents of brothers Paul and Raymond DEMERE, both Captains in the British Army but natives of France, who had come to the Georgia colony with the British in the 1700’s). Or maybe Peter had learned by then that paperwork in America, especially for immigrants, could be a much more casual proposition than was permitted in the Old Country.

According to the 1858 Savannah city directory, Peter Demare lived at 15 Walnut Street (near Harrison) in Savannah. But by May of the next year he and his family had moved to the southwest corner of Bay Lane and Jefferson Street, down by the Savannah riverfront in the Franklin Ward. (Today his building is gone and this is now the location of a nightclub made notorious by John Berendt’s 1994 nonfiction book, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil).

There Peter had a shop and worked as a wheelwright (making wheels for wagons, carts, and other vehicles) with his partner, John F. RUTZLER, a blacksmith. Peter was a registered voter and evidently an upstanding businessman, with friends among the other German immigrants in the mixed (partly Irish as well) ward, including George and Eliza OTT (natives of Hesse-Darmstadt), his next-door neighbors. George (born 1812 in Mombach near Mainz; died in Savannah October 1874), was a dealer in liquors who ran a “bar room and beer saloon” at Bay Lane & Whitaker Avenue, and was first foreman of the Germania (No. 10) fire department engine house on St. Julian Street, near Franklin Square.

The 1860 Federal Census, taken 27 July of that year, shows Peter Demare (age 40) and his wife Sophia (25) prospering. Their personal property was valued at $300 and they were the parents of two small children, Catharine, age 4 (called “Katrina” or Catharina, in the German way, by her family) and Henry (probably baptized Heinrich), age 2, both born in Savannah. With them lived a 60-year-old woman named Caroline GIRTZ (GOERTZ?), like Sophia, a native of Hanover, Germany (who perhaps was Sophia’s mother?). In the same home (probably as boaders) lived Herman HELLMAN (a 22-year-old wheelwright and blacksmith from Prussia, he was probably an apprentice or helper in Peter’s shop), and Carl F. ELLERS (EHLERS) (a 40-year-old “Bar Room Keeper” from Hesse-Darmstadt, no doubt a friend and employee of the Otts, with a large nest-egg: $500 in personal property). Next-door were George and Eliza Ott, doing very well by his “Bar Room” (he owned $3,000 in personal property plus $3,000 in real estate), and their several children (Anna, age 20; Julia, age 13; Peter, age 3—yet another little boy named after friend and neighbor Peter Demare?; and Eliza, age 1). With them too boarded Patrick Kelly, a 35-year-old laborer from Leitheimer, Ireland with no savings or property.

Why Peter Demare, after arriving in New York, decided to head to the Deep South and settle in Savannah, Georgia, I may never know. Perhaps he was drawn there by a description of the good business opportunities for a wheelwright in a thriving coastal port town. In 1847 the Central of Georgia Railroad had been completed, with Savannah as its eastern terminus. This marked the start of Savannah’s “antebellum zenith.” Business boomed, profits soared, and Savannah experienced sudden and unprecedented growth as it exported to the rest of the world cotton, tobacco, rice, corn, lumber, and naval stores (all produced with Southern slave labor). The city’s population bloomed, gas lighting was installed, while hospitals, churches, orphanages, water works, new cemeteries, and luxurious mansions were built as many new fortunes were made. Savannah was one of the important East Coast cities of the United States during that time, and was praised by many visitors as the most beautiful and tranquil city in America, with magnificent trees, gracious squares, stylish and tasteful architecture, and wonderful charm.

In addition to the good economic prospects, perhaps Peter had been swayed by the advice of relatives or friends who had earlier settled there and found Savannah and its community of German immigrants congenial. From its colonial beginnings, Georgia was intended to be a haven for persecuted religious sects and needy and poor people of all nationalities; it welcomed people of all religions except Catholics, who were considered by the English authorities to be the main persecutors of those seeking Georgia’s refuge. Among the colonists were the group of German Protestants called the “Salzburgers;” driven out of Europe, they established the settlement of Ebenezer about 20 miles upriver from Savannah in the 1730’s (today this area is known as Springfield, Georgia). The group of German Moravians who figured so importantly in the story of John Wesley and the development of the Methodist Church in America were also an early part of the area. Savannah, the oldest city in Georgia, was from the start a melting pot of foreigners, including Germans, Highlander Scots, English, Irish, French, and Portuguese. By the time Peter Demare lived in Savannah (perhaps mindful of his own Huguenot heritage?) he would have found there many welcoming and familiar institutions, including the Turn Verein (Savannah’s chapter was established in 1856) and other German fraternal organizations, the German Volunteers (a militia group organized in 1845), and German-run fire engine companies, just as there were in the many northern U.S. cities with substantial German populations.

Judging only by his cozy domestic and business situation conjured up by the July 1860 census, Peter’s choice in heading South and establishing personal ties there would seem to have been favored by fortune.

But he had ignored the “peculiar institution” of slavery and the ominously gathering clouds of larger U.S. political events to his peril.

Sophia was pregnant with their third child when the first Southern state, South Carolina, seceded from the Union on 20 December 1860. The break was received with enthusiasm and excitement in Savannah, where meetings were called to ratify the action. Flags were hoisted and military units volunteered their services to the state. Two weeks later, on 3 January 1861, Georgia Governor Joseph E. Brown ordered State militia troops to seize Fort Pulaski, a large brick structure thought to be impenetrable, guarding the mouth of the Savannah River. Three companies of the First Volunteer Regiment traveled by steamer from Savannah to Cockspur Island and, when the one elderly U.S. sergeant stationed there made no defense, marched into Fort Pulaski “with drums beating and colors flying” and “captured” the fort in what has been termed “the first belligerent act of the rebellious South.” Many of the 20,000 inhabitants of Savannah at the time disagreed on the wisdom of seizing the Federal fort. But when Georgia too seceded from the Union on 19 January 1861, the die was cast, and Savannah was jubilant. Fort Pulaski was transferred to the Confederate States of America and people of all stations in the Savannah area prepared to defend it, and themselves and their city. Slave labor was used to erect defenses. With the bombardment of Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor, South Carolina the following April, the Civil War began in earnest.

Peter and Sophia became the parents of a daughter that spring who was baptized Caroline Charlotte by Rev. J. Hawkins on 30 June 1861 at the Lutheran Church of the Ascension in Savannah’s Wright Square (the church that was established by the German “Salzburgers” of Ebenezer settlement in the 1700’s). It would seem that Peter and Sophia were not well-known to the Reverend, as their names were listed in the church’s baptismal record as “Peter & Sophia S. Denny”).

Savannah's Wright Square (looking toward the river) as it looked in 1909.

The Lutheran Church of the Ascension is on the right

(with spire, not clock) and has been at that location since 1771

but this photo shows the 1875 renovated version,

still in use today, which was

built upon the 1844 side walls and foundations.

It was about a 10-minute walk from the Demare home to the church.

Library of Congress Panoramic Photographs Collection

And so began the Union occupation of the fort and the Union Naval blockade of Savannah. No longer could exports of cotton and other goods make their way to the outside world, while the simple commodities of everyday life grew scarce in the city. Savannah men continued to go away to battle, while Savannah women endured privations, tedium, and tension, rolled bandages, raised money for charities, and formed knitting societies. Anything Yankee was vilified. It was a dangerous time to speak aloud of the Southern Cause in anything but loyal terms. Meanwhile, Savannah parents by December had to prepare their children for the possibility that Saint Nicholas might not make it through the blockade to deliver presents that year.

It is not known what role Peter Demare played in the war during this time. He may have been exempt from military duty by virtue of his age and his dependent family, or due to his occupation as a wheelwright being considered vital to the maintenance of the troops and/or the city. In 1863, as the war dragged on and the blockade endured, a third daughter was born to Peter and Sophia on the 1st of October. She too was baptized in the Lutheran Church of the Ascension in Wright Square, this time by the Rev. D. M. Gilbert, on 29 October 1863. She was given the name “Frederica Margaretta” (Frederike Margaretha) as recorded in the church register, where this time her parents were identified only as: “—— Demaree.” She would be called “Maggie” by her parents, but would be known as Margaret Demare as an adult.

The following April (1864), during the last grim year of the war, Company A of (Symons’) Georgia Reserves (the Chatham Siege Artillery) was inducting men of Savannah for the duration of the war. On 16 April a “P. Demere” was enlisted on the muster rolls of this Company A, along with his old friend, C. F. Ehlers (both were enrolled as Privates). The company was stationed at Oglethorpe Barracks in Savannah under the control of the Provost Marshall, but conditions were less than ideal. “The arms have been but recently furnished & the men have not yet put them in proper order,” wrote the clerk in June. “The company is regularly drilled. Many of the men are detailed [i.e., pulled away in small groups or individually for other tasks] by those having no authority to do so.” P. Demere was noted as having been absent from 16 April to 30 June: “Never reported / absent without leave” was the notation for this first muster period.

At the same time her husband was being drafted, “Sophia Demere” filed an application for a retail liquor license for a “store” at the corner of Jefferson & Bay streets (their home and shop), which was granted on 25 April 1864. She signed her name “Sophie Demare,” and the character witnesses were Charles Ehlers and Johann Helt.

The second muster roll of Symon’s Reserves for the period of July and August 1864 indicated that “P. Demere” had again been absent from duty at Oglethorpe Barracks, with the remarks: “Absent sick.” During these summer months Union Major General William Tecumseh Sherman had been fighting his way south from Tennessee into Georgia in his campaign to take Atlanta, which he accomplished by early September.

On 10 September the following item appeared on page 2 of the Savannah Daily Morning News:

We have received from Mrs. Sophia Demre, [sic] corner Bay and Jefferson streets, a sample of Lager Beer. The article is of excellent quality and a good tonic. Mr. H. H. Eden is agent in Savannah.

Evidently the young mother of four with the sick husband felt the urgent need to earn money for her household—no doubt with a little help from her friends, the Otts and Carl Ehlers. The city at this time was described by one person as “a city of ladies,” with almost all of its men absent, serving at various fronts in the war.

The third and last muster roll of Symons’ Reserves covered the months of September and October 1864, and again “P. Demere” was marked as “Absent,” “Sick at home.”

On 15 November General Sherman left Atlanta with approximately 62,000 Union men and began his infamous “March to the Sea,” burning and plundering his way across the Georgia countryside, deliberately intending to “make Georgia howl.” His goal was to reach and conquer Savannah.

Sherman’s approach caused distress and upheaval among the war-weary Savannah residents. Slaves became unruly; the southbound Gulf trains carried refugees and invalid soldiers away, while inbound trains brought thousands of ragged and wretched Union prisoners from Andersonville and other camps, taxing city resources beyond their limits. As the days wore on, the atmosphere in the city would became one of “expectant terror.”

On the 28th of November Sherman’s approach prompted a call from the mayor of Savannah for all men capable of bearing arms to report and be organized for defending the city. The Savannah Morning News wrote, “The old can fight in the trenches as well as the young...let no man refuse; and if any do, let us know his name.” But manpower to defend Savannah had already run out. By 10 December when the Union Army had the city in its sights, Confederate General W. J. Hardee had less than 10,000 men to meet the foe. Sherman demanded on 17 December that Savannah be surrendered, but was refused. Meanwhile, Hardee was laying pontoon bridges to allow his men to escape across the river in retreat to South Carolina. They (along with some number of women and families) effected a stealthy evacuation during the night of 20-21 December.

The following day, 21 December, Savannah surrendered to Union General Geary, who marched into the city and made his headquarters at the Central Railroad Bank. General Sherman arrived in Savannah itself on Christmas Day, having sent the following oft-quoted telegraph to President Lincoln:

“I beg to present to you as a Christmas gift the city of Savannah, with one hundred fifty heavy guns, also about 25,000 bales of cotton.”

The Union troops swarmed into the city and set up their camps in the squares. They put a stop to the initial looting being done by riotous crowds of “Irish and Dutch women, negroes and the thievish soldiers” they caught breaking into shops and “setting fires to property.” They began harvesting rice from the surrounding plantations to feed the city, and established a newspaper. They commandeered the Lutheran Church of the Ascension for a hospital. Cushions from the wooden pews were used as beds, and the pews themselves were burned as firewood. This building and others were extensively damaged. But it is said that Sherman spared Savannah from total destruction because of its beauty.

For Savannah, once Union troops arrived, the war was effectively over (the final surrender of South to North would arrive the following spring). On 28 December a meeting of citizens at Masonic Hall led by the mayor adopted resolutions to “lay aside all differences” and exert “best endeavors to bring back the prosperity and commerce we once enjoyed.” But Savannah was all but bankrupt. Its men were gone or dead; its women were standing in long lines to receive food rations from Union soldiers. The following month, on 27 January, a fire sparked in a stable destroyed over 100 buildings, all but completing the city’s demoralization.

After the Civil War, the South under Republican control began to rebuild its railroads and once again produce cotton. Exports from Savannah began moving again and exceeded $50 million in 1867, three years after the war’s end.

But the Demares had had enough of the South.

How had the Demares fared during the last days of Confederate Savannah? Had Peter been forced from a sick bed into a military unit? Had the family fled the city before Sherman’s army arrived, or had they stayed on during the occupation? Did they number among the Irish and Germans who were particularly singled out by one Union chaplain as a portion of the population to whom “the old [U.S.] flag is an emblem of hope and a signal of salvation”? Were they still in town in January, 1865 when the Northern cities of New York and Boston sent three charity ships of food supplies for the hungry women and children of Savannah? And what were their own true feelings about the Confederacy and its Lost Cause? I do not yet know.

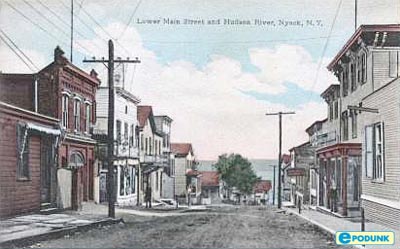

The next documentation of the family I have found is in the 1870 census, showing them living in Nyack (Rockland County), New York on 10 June. Nyack lies on the west bank of the Hudson River (much as Savannah lies on the Savannah River), about 25 miles north of New York City, but Nyack had never been an important port town. Prior to the Civil War, it had been an area notable only for farming and boat-building, but in the years immediately following the war’s end, factories moved in and the town grew larger and more industrialized. The family is here described by the census-taker as follows:

Demara, Peter, age 48, Wheelwright, born in Nassau, of foreign-born parents; a U.S. citizen

Katrina, age 14, Keeping house, born in Georgia, of foreign-born parents

Henry, age 11, born in Georgia, of foreign-born parents

Caroline, age 9, born in Georgia, of foreign-born parents

Maggie, age 7, born in Georgia, of foreign-born parents

Jacob, age 4, born in New York, of foreign-born parents

Next-door to them, the only Germans nearby, lived Christian DIEDRICK, a 59-year-old laborer, his wife, “Wilhemina,” 47, and a 14-year-old boy named John FROUM, all from “Wirtemberg” and described as being unable to read or write.

I can surmise from this census that the family moved from Savannah by 1866 when Jacob had been born in New York State. But why wasn’t Sophie with the family on this 1870 census? Had she died, perhaps in childbirth? And what had brought them to Nyack in particular? Was there a conscious connection between Peter Demare and the Huguenot roots of the area, centered around Demarest, New Jersey (settled by French Huguenot immigrant Davis de Marets in 1663), just 10 miles south? This is a tantalizing idea, but unfortunately my search has yet to turn up answers.

The 1880 census shows the family even further fractured:

“Henry Demaia” (age 21, born in Georgia, parents born in Nassau [sic]) is shown to be a “Farm Laborer” living with the family of farmer Richard SWARTWOUT [sic] (age 50) and his wife Priscilla (40) and their four sons in Clarkston, Rockland County, New York. Nearby, “Jacob Demaia,” 14-year-old laborer (born in New York, parents born in Nassau [sic]) lived with 30-year-old Louis SEBRICK, a Canadian, and “Keeper of Pic Nic Ground.” Beyond them lived George SWARTHOUT, 43, another farmer, with his wife Arietta, and their own four children, a niece, and a servant.

“Margaret Demara” is described as a 16-year-old “Servant” (born in Georgia, parents born in Germany) in the household of clergyman George H. WALLACE (age 31, Canadian, of Scottish parents), his wife Isabella (age 24), and their twin one-year-old sons, George and William, near DePew Avenue in downtown Nyack, New York. Rev. Wallace was the pastor of the Nyack Presbyterian Church from October 1877 to 1880.

Lower Main Street, Nyack, New York,

looking toward the Hudson River, early 1900’s.

Where were the other two sisters, Catharina and Caroline? And where were their parents, Sophie and Peter? Because vital records were not yet being kept consistently in New York at that time, finding documentation of their deaths and burials has proved to be difficult.

But the search continues....