A Story of Two Fisher Families

by Michelle Stone

December 2014; updated January 2015

This true genealogical tale sprang out of years of research undertaken by Jo Ann (Johnson) Fisher, Sydney Nettleton Fisher, and Michelle Stone, and was sparked by a recent online discovery of an old book on the early history of Francestown, New Hampshire. Just a few key sources are cited at the end of this story. This tale is not intended to be a fully documented research paper—just a short, interesting, and true yarn about some Fisher ancestors. For more information or details on sources, contact the author.

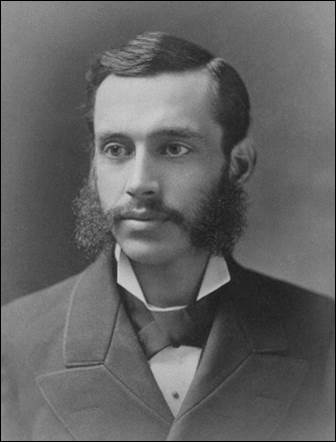

Mary Georgiana Shaw (her mother was a Fisher) and Dr. John Crocker Fisher

The year was 1878; the month was December. Dr. John Crocker Fisher, age 28, had been stationed in charge of the Marine Hospital in Mobile, Alabama since October when he was suddenly ordered to proceed to the city of Cairo, Illinois at the junction of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. Appointed as an assistant surgeon with the U.S. Marine Hospital Service the year before, he was used to being transferred from place to place by the federal government to assist with the medical needs of U.S. marines and seamen. Increasingly the Hospital Service personnel were being called in to assist with public health emergencies such as the devastating yellow fever epidemic that had swept through the Mississippi River Valley that summer. The officer in charge at Cairo had died of yellow fever and now Dr. Fisher was being sent north to take over his duties. The day after his train arrived in town he appeared at the office of the Collector of Customs in Cairo to pick up his salary ($100 a month) and a reimbursement of his traveling expenses.

“Your name is Fisher, is it?” said the Collector. “Well, that’s my name, and I have a son whose name is the same as yours: John C. Fisher.”1

The two men chatted briefly as Dr. Fisher presented his vouchers, but the office was busy and neither man had much time just then. The Collector generously invited the young stranger to dine at his home in the Third Ward on Christmas Day. It was a welcome invitation, with Christmas near at hand and Dr. John Fisher being far from his family back in Warsaw, New York.

Christmas dawned quietly as an Arctic cold snap had set in with a vengeance. The entire Mississippi River from Saint Paul, Minnesota to Cairo had frozen over and was, for all practical purposes, closed. Temperatures had stayed at or below zero the day before, and would only grudgingly climb to the teens later on Christmas day. For much of the mid-West it was the coldest point of the waning year. Still, when Dr. John Fisher ventured out to the Collector’s home that Wednesday, it was a sunny day with only a light wind.

At dinner, Dr. Fisher met the whole extended family assembled inside the warm Fisher home.2 There were the Customs Collector, George, a lawyer in his mid-40’s, and his wife, Susan, in her late 30’s, both natives of Vermont. There were Susan’s younger unmarried sister, Julia, aged 31, and their widowed mother, Amelia Copeland, who both lived with the family. There were George and Susan’s two children, Nellie, 11 years old, and the aforementioned John C. Fisher, a boy of eight (who would grow up to be the editor and publisher of the Cairo Citizen newspapers). And there was Miss Mary Shaw of Grinnell, Iowa, age 23, George Fisher’s sister Susan’s daughter, who was spending the winter with her uncle and his family.

They must have talked about the frozen river and the cold weather, and about the yellow fever epidemic which had gripped Cairo that year (62 officially recorded deaths, probably hundreds more unrecorded, while thousands had fled the city in panic). With the first frosts in October the sickness had diminished, and Dr. John’s fears about taking over the Cairo position were relieved. (No one yet knew at that time that yellow fever was transmitted by mosquitos, but they realized it was somehow related to the weather.) They must have talked about Cairo, as the lawyer and his wife would have kindly introduced their new friend to some of the facts and recent news of their city, at that time a major U.S. port and transportation hub.

And they talked about themselves and their families. Dr. John no doubt mentioned his father and stepmother back on the farm in western New York State. And as the two men tried to puzzle out their common surname, he would’ve told the story of how his great-grandfather, Deacon Samuel Fisher, had been born in northern Ireland and had emigrated from there at the age of 18 (“a tough and fearless Scotch boy”3) in 1740 on what was known to all of his descendants as “the starved ship”—a ship that ran out of food and water before it reached America. The travelers were forced to resort to cannibalism to stay alive. The boy Samuel Fisher was the unlucky one chosen by lot to be next eaten just before another ship was sighted and help arrived. Samuel, a weaver by trade, then worked as an indentured servant for a year or two in Roxbury, Massachusetts to pay off the debt for his passage to New England. When freed of that obligation he walked the 70 miles to Londonderry, New Hampshire, a town founded by his own ethnic group (Protestant so-called “Scotch-Irish” immigrants from Londonderry, northern Ireland); founded perhaps by people or families he knew. There he prospered as a farmer, a respected leader in his community, and a deacon in the Presbyterian church. (As one source said, he was “tall, large, grave, commanding, fearless, and of strong mind. No firmer [C]hristian could be found. He knew WHAT he believed, and WHY, and taught it at home and abroad.”) By the time of his death in 1806 Deacon Samuel Fisher had married three times, had fathered twelve children, and was survived by 76 grandchildren and 53 great-grandchildren.

But as Dr. John later wrote about his Christmas Day meeting with the Fishers in Cairo, “We found we were not related” because the Fisher ancestors of the Cairo Customs Collector and his niece had come to America from England, not from Ireland.

Still, the day was a fruitful one, as Miss Mary Georgiana Shaw found something attractive in the handsome young doctor and he likewise was struck by her. They furthered their acquaintance during the time they both remained in Cairo. In September 1879 Dr. John C. Fisher was transferred to a position as assistant to the Surgeon General in Washington, D.C. Eight months later, on May 11, 1880, he and Mary were married in her home town of Grinnell and then she followed him to Washington where they made their first home together. Their happy marriage produced three children and lasted 52 years until his death in 1932.

These two Fisher families may not have been related before John and Mary tied the knot. But, unknown to Mary and John, their families’ paths had crossed before....

The year was 1770, six years before the signing of the Declaration of Independence and 108 years before Dr. John met Mary on Christmas Day. In Londonderry, New Hampshire, Dr. John’s great-grandfather, Deacon Samuel Fisher (of “the starved ship”), then in his late 40’s, was saying goodbye to his oldest son, James. James was 19 years old, “but mature and vigorous like one of riper age.” He and his father had been to visit the area that would later be known as Francestown, New Hampshire, about 35 miles west of Londonderry, the year before. Deacon Samuel Fisher had been one of 17 men of Londonderry who had made a large purchase of land there (about 5,000 acres, known as the Wallingford Right) in 1766. The plan was to divide up the land, cut a road through it, settle on it, and offer parcels for sale. Now James was to strike off into the forest and make a farm on Samuel’s portion. Several other sons of the Londonderry purchasers were doing the same pioneering:

“Thus James Fisher, William Starrett, Oliver Holmes, and Isaac Butterfield all excellent men, moved their families here in 1770... Log-houses and barns were built here and there, and all things wore the look of determination and hope. This year also ‘David Lewis’ saw-mill’ was completed and set at work, to the great joy of the settlers, not only of those just coming in to build, but also of those hoping to replace ere long their small, well-worn log cabins with more desirable residences.”

At the first official town meeting, held July 17, 1772, the men of Francestown voted to have preaching that year sheltered “in James Fisher’s barn.” Subsequently they also held their official town meetings in James Fisher’s barn, as recorded by the town clerk. “As there was for several years from his settlement in 1770 no house where the village now is, the house of Mr. Fisher was the most central, and his doors were generously and often thrown open for the various gatherings of the settlers.” James Fisher was described as “a man of public spirit, having a tender interest in the future of the little community.” He had the honor of making the first public gift to Francestown in November 1772, when he granted four acres of ground for a town common, a future meeting house site, a training field, and a town cemetery, “being the East End of the lot which I [purchased] from my Father Samuel Fisher.” James Fisher contributed much to Francestown: “was large-hearted and generous; was very religious and later became an elder in the Presbyterian Church and a Deacon in the Congregational church (in 1790). He was held in high esteem by all who knew him; and did not lack such trusts and honors as his town could confer.” In 1775 he was voted a Selectman; in 1785 he was voted into the position of Town Clerk; in 1789 he was voted onto the committee to set up a school district, and in 1800 he was on the committee to draw up the plan and estimate the cost of a new meeting house.

The “Scotch” pioneers from Londonderry were said to have been the first settlers of Francestown and for many years they outnumbered the “English” settlers who arrived. “James Fisher was a Scotchman and a strong Presbyterian, but he joined heartily with the ‘English’ part of the settlement to promote the public good. The Scotch settlers “owned the best part of the town, and held most of the prominent offices. They were chiefly the soldiers of the field, the committees of safety, the military leaders, and the men to be consulted on affairs in general. They were characterized by a force and fearlessness, calculated for pioneers. Carson, the Dickeys, the Quigleys, McMaster, Parkinson, James Fisher, William Starrett, and most others of the town's foremost men, were of the Scotch race.”

But early on, there was another man named Fisher whose actions were also recorded in the town records of Francestown along with those of James Fisher:

--At the same first town meeting when it was voted that preaching would be held in James Fisher’s barn, Nathan Fisher and William Butterfield were elected “Fence vewuars [viewers] and presers [pricers, i.e. appraisers] of damage”

--On July 22, 1771, 39 men signed the petition to start a new township called Francestown; signatures included those of both Nathan Fisher and James Fisher

--On August 31, 1772 another town meeting was held at “James Fisher’s barn”

--Oct. 1, 1772 a meeting to draw jurors was held in James Fisher’s barn

--On December 2, 1772 Nathan Fisher signed a petition

--And at a meeting in March 1773 it was “Voted that the pre[a]ching Shall be Heald at James [F]ishers house or barn for present Year” and also “Voted that Nathan [F]isher is to Bo[a]rd the m[i]nister and Keep his H[o]rse for five Shillings an[d] Nine P[e]nce Lawfull money pr Week.”

It should also be noted that both Nathan Fisher and James Fisher signed The Francestown Resolves in October 1774, being a bold declaration and petition regarding liberties, rights, and the town’s political stance in the face of the oncoming war with the British.

Who was this Nathan Fisher?

He was a great-grandson of Anthony Fisher III (1623-1670), who was born in Syleham, Suffolk, England and came, at about the age of 14, with his parents and siblings, to Boston, Massachusetts in 1637. This family was a part of the great Puritan Emigration to New England of English subjects seeking religious freedom. Later Nathan, when he was about the age of 25, came from Dedham, Massachusetts to Francestown in 1770, about the same time Dr. John C. Fisher’s great-uncle James Fisher arrived there. And Nathan Fisher was the second cousin (five times removed) of Mary Georgiana Shaw Fisher. Anthony Fisher, the immigrant ancestor of the English Fishers from Syleham, was the fifth-great-grandfather of George Fisher the Customs Collector of Cairo, Illinois and his sister, Susan Fisher Shaw (Mary’s mother).

Both these “Irish” (who were really “Scotch”) Fisher pioneers and these “English” Fisher pioneers put down roots and had children and grandchildren in Francestown, New Hampshire who lived and worked in close proximity over generations. Additionally, Nathan Fisher had a brother (Abner), a sister (Abigail), nephews (Seth, Ezra, and Thomas) and other relations (“King David” and Moses Fisher) who likewise came from towns in Massachusetts to settle in Francistown between 1780 and 1785. “At the close of the Revolutionary War, however, men of the English race began to come here more numerously than before, so that at the time of the union of the two churches (1790) the two races were about equal. Men who served in the army from Massachusetts came here to make a home; some of them before the close of the war. By 1800 the English far out-numbered the Scotch, but by that time the two races in this town had become so united, by intermarriage, business intimacy, and church fellowship, that the distinction of races was little noticed.” And, of course, the Revolutionary War had uniquely knit all foreigners and subjects of the various distinct parts of Great Britain and the colonies into one common category of citizen: now they were all Americans.

Francestown, New Hampshire, a town forged out of the wilderness by hardy settlers, for a certain period long before Dr. John and Mary were born, was a nest of jumbled English and Scotch Fisher relatives of theirs. It is highly doubtful that John and Mary ever knew about it, or had ever even heard of Francestown, New Hampshire (today its population is under 1,500 souls). Yet the connections had been made. The DNA of two families named Fisher had already rubbed shoulders and no doubt shaken hands and hoisted a draught together in pre-Revolutionary America before two young, unknowing descendants met as strangers over a Christmas table in 1878 and fell in love.

And who can tell how often it has happened before or since? Who knows, in fact, how or why the “Irish” Fishers got to northern Ireland from Scotland anyway—or perhaps, how they got from England to Scotland before that? All we know is that it can be fun to speculate until an ambitious genealogist can tackle uncovering more facts about the deeper backstory.

---------------

1 A Fisher Family History and Autobiography by Dr. John Crocker Fisher (1850-1932), Michelle Stone, editor (2005). Dr. Fisher, who wrote this memoir late in his life, included this direct quotation from George Fisher, the Collector of Customs at Cairo. It is not certain if he recalled it verbatim or was indulging in a bit of poetic license in reconstructing the scene, but I include it here (emphasis added was mine, for clarity). Every good story is made better with dialog.

2 The June, 1880 Cairo census, taken a year and a half after the Christmas dinner, showed these people living together in the George and Susan Fisher household in Cairo’s Third Ward. This is the one point in the story not based on sure fact, but where I have made an assumption: that everyone in the household of 1880 attended the 1878 dinner, including Mrs. George Fisher’s sister and mother—but of course their actual presence at dinner is not known for sure.

3 This quotation, and the many that follow, are taken from the book History of Francestown, New Hampshire, From Its Earliest Settlement April, 1758, to January 1, 1891 With a Brief Genealogical Record of All the Francestown Families by Rev. W.R. Cochrane, D.D. of Antrim, N.H. and George K. Wood, Esquire of Francestown, Published by the Town, Nashua, N.H., James H. Barker, Printer (1895). This book, which I recently found online, contains the fascinating story of how Francestown was settled, including the genealogies of all the early Fisher pioneers.

A few other key resources (these once-rare books can now be viewed online by searching in Google):

The History of Londonderry, Comprising the Towns of Derry and Londonderry, New Hampshire, by Rev. Edward L. Parker, Perkins and Whipple, Boston (1851).

History of the Town of Warsaw, New York, From Its First Settlement to the Present Time; With Numerous Family Sketches and Biographical Notes by Andrew W. Young; Sage, Sons & Company, Buffalo, New York (1869). Subsequent generations of descendants of Deacon Samuel Fisher were also pioneers themselves as they pushed out of Londonderry, New Hampshire into new wilderness frontiers in Warsaw, New York and Nova Scotia, Canada, among other places.

History of Windsor County, Vermont with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of its Prominent Men and Pioneers by Lewis Cass Aldrich & Frank R. Holmes, editors, D. Mason and Company, Syracuse, New York (1891). Some of Mary Georgiana Shaw’s maternal Fisher ancestors were pioneers migrating from Massachusetts into the woods of Vermont.

History of the Town of Springfield, Vermont with a Genealogical Record by C. Horace Hubbard and Justus Dartt, George H. Walker & Company, Boston, Massachusetts (1895).

The Fisher Genealogy: Record of the Descendants of Joshua, Anthony, and Cornelius Fisher of Dedham, Mass., 1636-1640, by Philip A. Fisher, Massachusetts Publishing Company, Everett, Massachusetts (1898).

Paper on Yellow Fever [in Cairo, Illinois, 1878] from Illinois Public Health Preparedness/Public Health Learning:

https://www.uic.edu/sph/prepare/courses/PHLearning/resources/yellowfever.pdf

| Home |